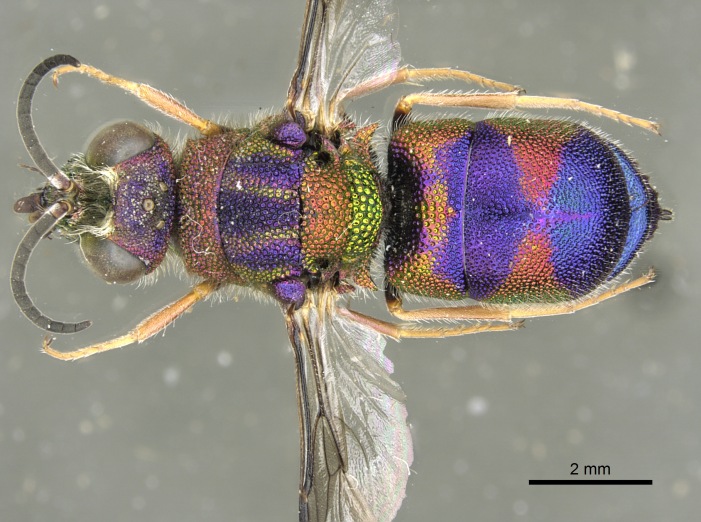

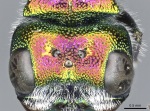

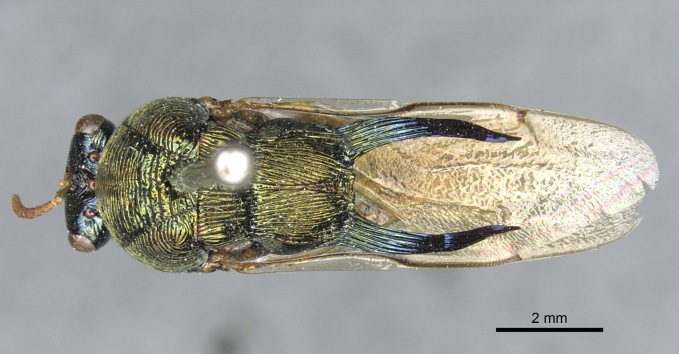

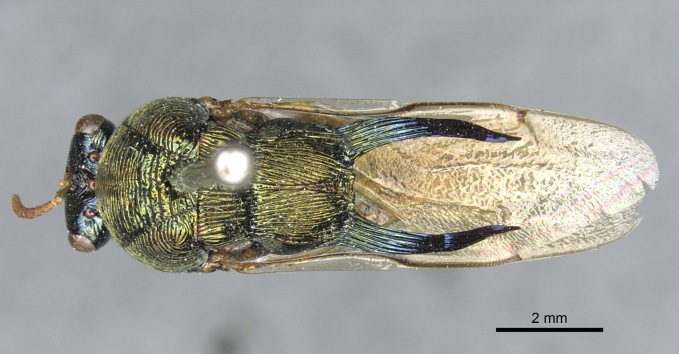

Today’s offering is the spectacular Kapala splendens, a Neotropical eucharitine wasp. Some notes on the boggling biology of these precocious parasitoids, a small gallery of images, and – of course – some tasty references. Remember to view the full-size photos for the best detail!

The Eucharitidae is a family of parasitoid wasps belonging to the hugely diverse superfamily Chalcidoidea. Members of this morphologically diverse family are often distinctive (though the characters that distinguish them from related groups were only relatively recently quantified), with a tall, humped mesosoma, sometimes armed with long, backwards-pointing spines, a small head, a long, stalked waist, and a small, low-slung gaster. All are pleasing to look at (the name Eucharis comes from the Greek for ‘pleasing’) and many are highly modified and bizarre in form; all have fascinating life-histories. There are over 400 species in three subfamilies, found nearly everywhere in the world besides the poles, New Zealand, and certain isolated islands. Every known species is a specific parasite on ant larvae or pupae.

The genus Kapala, to which our splendid friend belongs, is the most dominant and diverse of the Neotropical eucharitines, with around 60 species.

The first member of the family was described in 1787 by Fabricius, as Cynips adscendens, transferred later to the genus Eucharis established by Latreille in 1802.

Eucharitids lead strange lives, from hatching to oviposition. Adults exit from the host ant nest after variable (and poorly known) periods of time, with the males often emerging first. The machos await the females’ arrival, some species calmly waiting on nearby vegetation, others swarming agitatedly a few feet in the air in groups that can reach the hundreds. As soon as the females appear, the males jump on them and get to business. Adult females emerge with all the eggs they will need already developed and waiting for fertilization. Emergence, insemination, and oviposition can occur on the same day, and sometimes even within the hour.

Partly because of this, the adults in most species probably never need to feed; the larvae, however, are voracious, consuming most or all of their hosts. Adults are probably also fed and tended by ants during their stay in the nest. I ate your baby sister, now feed me!

Many parasitoids lay their eggs directly into or onto the host, and when the larva hatches it has a plentiful supply of nutrition at the ready. Not so with eucharitids – even, surprisingly, in species that develop within their hosts’ bodies. Females oviposit in a wide variety of specific niches on plants: on leaf surfaces, within seed pods, in growing leaf or flower buds, in incisions in the tissue of leaves, beneath grass bracts, in flower sepals, and so on. Plants utilized range from grasses to Asteraceae to mangos. Some take the (already tripartite) interspecific interactions yet a step further, choosing oviposition sites that will favor the newly-hatched larvae’s chance of hitching a phoretic ride to a host colony. In one titillating species, Psilogaster antennatus Gahan, eggs are laid only near the freshly deposited eggs of a thrips, Selenothrips rubrocinctus (Giard). The thrips and the wasps hatch at the same time, and the wasp larvae hop on board (sometimes upwards of 50 per thrips) with no apparent harm to the carrier. What is mystifying is the lack of any known interaction between the thrips and Psilogaster‘s ant host.

It seems that oviposition sites for eucharitids are obligate relationships – they need the right plant, the right place, and sometimes the right stage of plant life. Therefore the parasitoids rely not only on the distribution of their host ants, but on the egg-plants as well. This double-jeopardy may be part of the reason why eggs are often laid in huge amounts – Clausen (1941) reports 4 million in a single tree – and also why eucharitids are a relatively poor natural control agent for ants, despite their efficiency when the right conditions are available.

The first-instar larvae of eucharitids are known as planidia, and while later on they will be living as the ultimate-couch potatoes, at this stage they are active, strongly sclerotized little terrors. ‘Little’ probably isn’t the right word. Even ‘minute’ barely does these <.013 mm crawlers justice. They need to find their way to a tasty formicid, and various species have many ways to do so. Some (parasites of ponerine ants) cast about until they find an appropriately moving target – sometimes a foraging ant, but sometimes a female of their own species arriving to oviposit on the same plant, a passing scorpion, or some other arthropod. If they happen to grapple onto an appropriate host, they’re in luck. Otherwise, they can hope that their unwitting vehicle stumbles across the right ants on its own. Other eucharitids, which parasitize formicine or myrmicine hosts, are lucky enough to hatch near a nectary or on/in a fruit to which the ants will come, seeking sugary goodness. Still others rely on a thrips or an auchennorhynchan intermediary to bring them to their host ants, which treat the carriers as prey or cattle respectively.

Once acquainted with its new ant friend, the planidium chooses a tasty spot and settles down to the business of growing. Those of the subfamily Eucharitinae latch on to the outside of the ant larva, while Gollumiellines and Orasemines are endoparasitic.

Most species feed while allowing the host to grow and even achieve a well-developed pupal stage before killing it. In almost every case, the eucharitid larva remains in its first instar until the ant molts and becomes a pupa. That doesn’t mean that it’s not growing though – in fact, the planidium increases enormously in size. Parker (1932) reported a 1000x increase in Stilbula cyniformis!

Once the host has entered the pupal stage and the planidium has molted, feeding increases rapidly and most or all of the hapless ant pupa is eaten alive.

After emerging as an adult, eucharitids are treated as welcome guests in the ant colony. How can a critter that looks so little like an ant be such an effective impostor? To us, the wasp is obviously an outsider. Ants, though, perceive the world very differently from humans. While many ants have eyes, only a few species are strongly visually-oriented. The world of ant communication is one of odors, and for the eucharitids, chemical (Wasmannian) mimicry is the chink in the colony’s exoskeletal armor. Semiochemicals are at the heart of many ant interactions, and if the parasitoid can smell like a sister, then to the ants, it may as well be. Indeed, several studies have shown that the cuticular hydrocarbons of certain eucharitids match those of their hosts by 70-90%. There are indications, though, that the ploy becomes less believable over time, as ant agression increases against older wasps and analyses have shown that older individuals have less similarity in their hydrocarbon signatures.

Eucharitids parasitize various groups of ants from several subfamilies. The genus Kapala, pictured here today, are known to attack ponerine ants of the genera Dinoponera (1 known host species), Hypoponera (1), Odontomachus (9), and Pachycondyla (5), and ectatommine ants of the genera Ectatomma (3), Gnamptogenys (4), and Typhlomyrmex (1). Kapala floridana supposedly associates with the myrmicine Pogonomyrmex badius.

Most eucharitids seem to be very specific in their host choice. Kapala, though, not only have a wide range of hosts as a genus, but at the specific level, with some species parasitizing several unrelated types of ants from different subfamilies. This flexibility, along with the ubiquity and dominance of many of their host ants, help explain Kapala‘s success in the forests of Central and South America. Walk softly, and chew on a big ant.

-

-

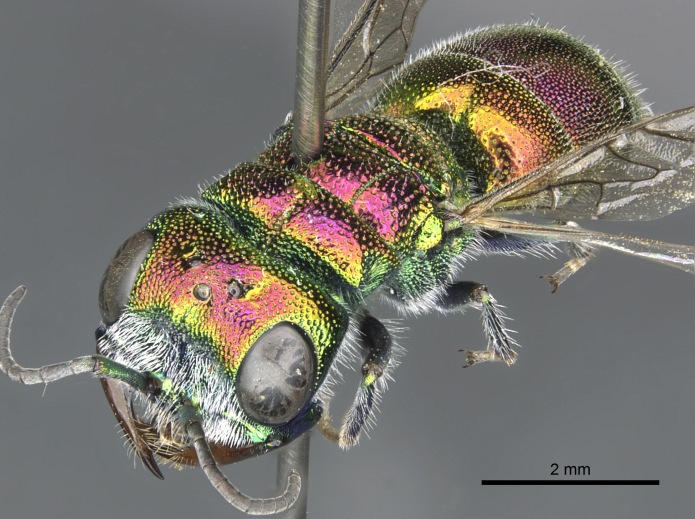

This large, brilliant species shows the bizarrely modified mesosoma characteristic of the family.

-

-

-

-

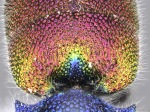

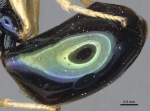

The small pronotum obscured dorsally by the head is one of the diagnostic characters of the Eucharitidae.

-

-

In the Eucharitidae, the prepectus lies in the same plane as the pronotum, and these sclerites are often fused.

-

-

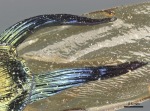

In the Eucharitidae, the metasoma is petiolate, with a very long, cylindrical petiole and relatively small gaster.

-

-

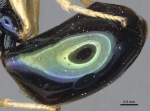

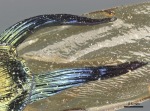

The form of the scutellar processes is important in distinguishing eucharitine genera.

-

-

The structure of the scutellar processes is important in distinguishing eucharitine genera.

-

-

-

Label information for the pictured specimen.

References (all available as PDFs).

Ashmead, W.H. 1904. Classification of the chalcid flies or the superfamily

Chalcidoidea, with descriptions of new specimens in the Carnegie Museum, collected in South America by Herbert H. Smith. Memoirs of the Carnegie Museum, 1: 225-551.

Clausen, C.P. 1941. The habits of the Eucharidae. Psyche 48:57-69

Darling, D.C. 1988. Comparative morphology of the labrum in Hymenoptera: the digitate labrum of Perilampidae and Eucharitidae (Chalcidoidea). Canadian Journal of Zoology 66:2811-2834.

Heraty, J.M. 1985. A revision of the Nearctic Eucharitinae (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea: Eucharitidae). Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Ontario 116:61-103.

Heraty, J.M. 1989. Morphology of the mesosoma of Kapala (Hymenoptera: Eucharitidae) with emphasis on its phylogenetic implications. Canadian Journal of Zoology 67:115-125.

Heraty, J.M.; Darling, D.C.1984. Comparative morphology of the planidial larvae of Eucharitidae and Perilampidae (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea). Systematic Entomology 9(3):309-328.

Howard, R.W.; Pérez-Lachaud, G.; Lachaud, J-P. 2001; Cuticular hydrocarbons of Kapala sulcifacies (Hymenoptera: Eucharitidae) and its host, the ponerine ant Ectatomma ruidum (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 94(5): 707-716.

Lachaud, J.P.; Cerdan, P.; Pérez-Lachaud, G. 2011. Poneromorph ants associated with parasitoid wasps of the genus Kapala Cameron (Hymenoptera: Eucharitidae) in French Guiana. Psyche 2012:1-6

Links:

http://www.nhm.ac.uk/research-curation/research/projects/chalcidoids/eucharitidae.html

http://hymenoptera.ucr.edu/eucharitidae

————————

The pictured specimen [BMNH(E)1015004] is the property of the Natural History Museum, London (BMNH).

All images and text contained in the above post are copyright © Z. Lieberman 2012. See bottom of page for usage guidelines.

———————–